The second story in a series by Fiona Wilton about exploring the mysteries of the Uruguayan sea. Read the first instalment here.

As the the start of spring beckons in the southern hemisphere, so a remarkable month of discovering hidden life on the Uruguayan seabed, draws to a close. Thanks to the Uruguay Sub200 expedition, aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute research vessel Falkor (Too), we have witnessed in real time an unknown ocean world at depths of hundreds, even thousands, of meters from the surface.

The groundbreaking difference for this underwater expedition – aside from the good humour, informative, and often emotional live commentaries from the scientists onboard – has been the SuBastian ROV, an underwater robot capable of diving to depths of up to 4,500 metres. Equipped with high-definition cameras, lights, robotic arms and sensors, the SuBastian can capture everything from tracks in sediment to wildlife in motion. It has been a game changer, giving everyone – including primary schools across the country – the chance to follow live, from their phone screens or computer, a form of ‘virtual diving’ as the robot travels through canyons, seamounts and rich marine ecosystems.

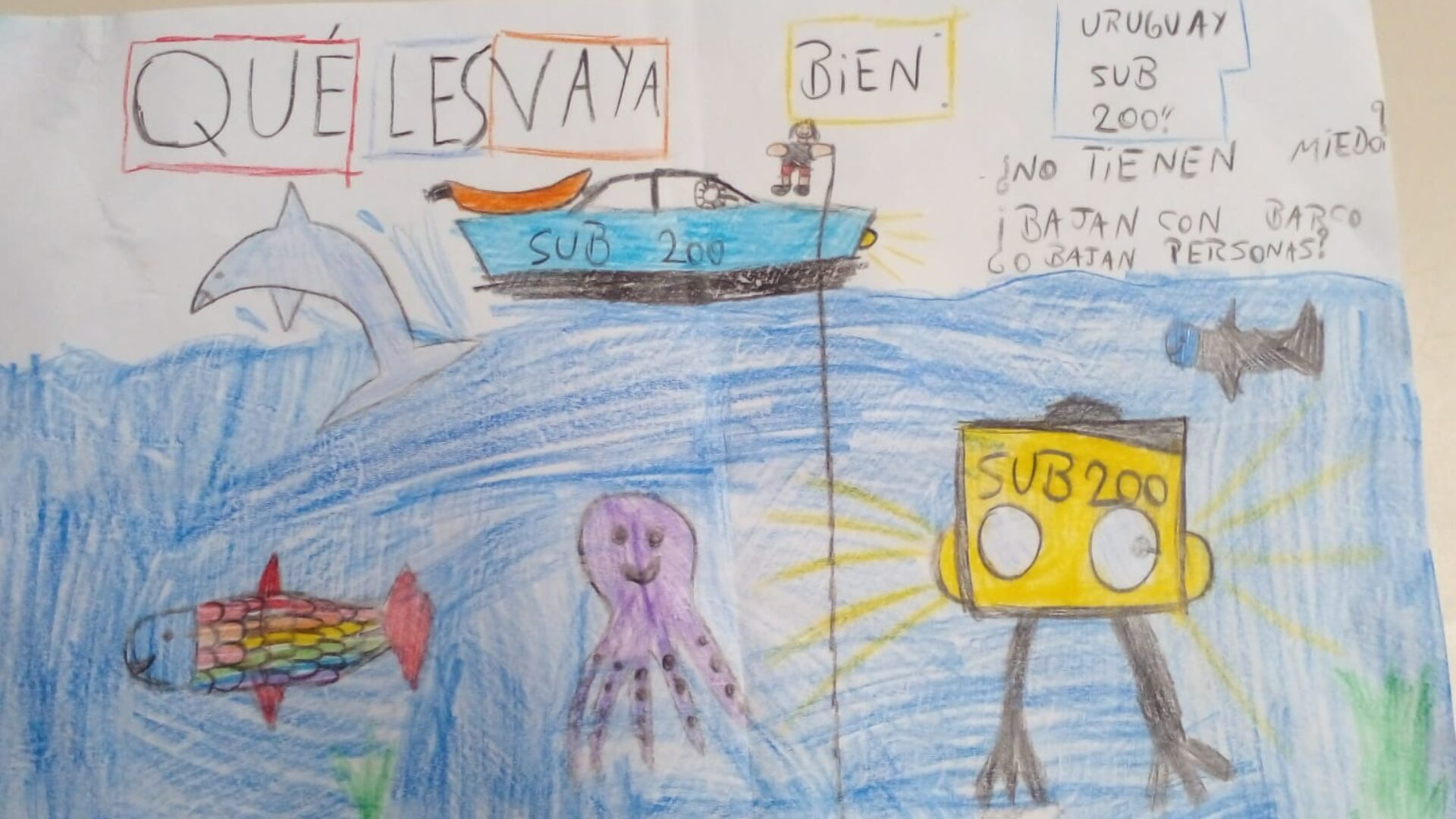

The Uruguay Sub200 vessels drawn by students from the Costa Azul and La Paloma schools in Rocha, in collaboration with Gaia’s partner Mar Azul

With SuBastian taking viewers down to 4,000 meters, eyes were wide open as we viewed flying ‘chanchitos’, or sea-pigs, a genus of deep-sea sea cucumbers, and dancing octopus. In shallower waters, we were greeted with coral gardens, sandbar sharks and lemonfish. The Ministry of Education and Culture’s initiative to broadcast daily summaries of underwater discoveries, have amplified this new connection to the ocean underworld.

From deep-sea rays (Amblyraja frerichsi) at 1,400 meters, to the presence of two six-gill sharks (Hexanchus griseus) at a depth of 300 meters, the observation of endangered or little-known species had reinforced the importance of Uruguayan deep waters. The mere appearance of species like the sunfish (Mola mola), which can reach over three meters on a diet primarily of jellyfish, confirms the biological richness of this area of the southwest Atlantic ocean.

For Uruguay’s researchers, the material obtained is key to advancing studies of biodiversity and ocean processes. For the country’s emerging roadmap and commitments for marine conservation, UruguayAzul2030 – explore them here – the findings are vital. For the public, the images are creating a connection with a sea and Uruguay’s marine biodiversity that was previously invisible.